Explore how reforming Pakistan’s civil service can transform governance. Learn about SMART civil service reforms—Specialised, Meritocratic, Accountable, Results-oriented, and Tech-enabled—for the 21st century.

Building a SMART Civil Service in Pakistan

A state survives not on speeches but on the machinery that delivers its promises. In Pakistan, that machinery is rusted. Pakistan’s civil service, often described as the steel frame of governance, is in reality showing deep cracks under the weight of outdated structures, rigid hierarchies, and rules that have remained virtually unchanged since the 1970s. At a time when society has been transformed by urbanization, globalization, and technological disruption, the bureaucracy continues to operate on a model designed for another era. This mismatch between national needs and administrative capacity is no longer just an institutional weakness; it has become a barrier to development itself. Civil service reform, therefore, is not an option—it is an existential necessity for the state and its people.

The history of reforms in Pakistan reveals both recurring intentions and chronic failures. Since the renaming of the Ministry of Planning and Development to include “Reforms” in 2013, there have been extensive consultations, studies of international best practices, and even presentations to prime ministers. A minor change was achieved in 2015 by raising the CSS age limit from 28 to 30 years, but most proposals remained on paper. Earlier efforts, including those under Dr. Ishrat Hussain, also emphasized performance agreements, yet were unable to break the inertia of entrenched interests. In essence, the country has spent decades diagnosing the illness but refusing the treatment.

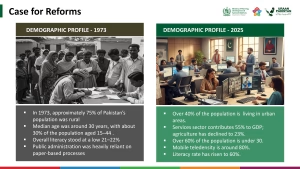

The need for reform today is sharper than ever before. In 1973, Pakistan was largely rural, paper-driven in administration, and had a literacy rate of just 21 percent. Today, over 40 percent of the population lives in cities, services dominate the economy, more than 60 percent of citizens are under thirty, and technology has become the backbone of governance across the world. Yet Pakistan’s civil service still clings to a colonial-era tenure-based model, designed more for administrative control than for innovation or results. The system is misaligned with national aspirations, disconnected from citizen needs, and vulnerable to inefficiency and corruption.

The need for reform today is sharper than ever before. In 1973, Pakistan was largely rural, paper-driven in administration, and had a literacy rate of just 21 percent. Today, over 40 percent of the population lives in cities, services dominate the economy, more than 60 percent of citizens are under thirty, and technology has become the backbone of governance across the world. Yet Pakistan’s civil service still clings to a colonial-era tenure-based model, designed more for administrative control than for innovation or results. The system is misaligned with national aspirations, disconnected from citizen needs, and vulnerable to inefficiency and corruption.

Global experience offers instructive lessons. The United Kingdom, Malaysia, and New Zealand have built performance-based systems with results delivery units and transparent promotion mechanisms. Singapore and the UAE attract top talent through competitive pay and digitized services, while South Korea and India have introduced AI-driven governance and citizen grievance platforms. Rwanda, Denmark, and Indonesia showcase how decentralization, diversity, and local empowerment can strengthen accountability. The common thread is clear: modern civil services are citizen-centric, merit-based, technologically enabled, and accountable through measurable results.

Global experience offers instructive lessons. The United Kingdom, Malaysia, and New Zealand have built performance-based systems with results delivery units and transparent promotion mechanisms. Singapore and the UAE attract top talent through competitive pay and digitized services, while South Korea and India have introduced AI-driven governance and citizen grievance platforms. Rwanda, Denmark, and Indonesia showcase how decentralization, diversity, and local empowerment can strengthen accountability. The common thread is clear: modern civil services are citizen-centric, merit-based, technologically enabled, and accountable through measurable results.

The methodology for Pakistan’s reforms has been carefully structured. Fifteen committee meetings, five sub-working groups, and consultations with private sector leaders, the army, and academia have ensured that proposals are not detached from ground realities. Comparative studies of regional and global models further enrich the framework. The process has gone beyond theoretical debate, drawing from performance-driven systems in the corporate sector and HR practices in the Pakistan Army, where psychometric testing, rigorous training, and objective promotion boards ensure alignment between roles, merit, and leadership.

Insights from institutions and sectors also highlight what Pakistan’s bureaucracy lacks. Corporate organizations link performance directly with individual KPIs and succession planning, while the army prioritizes “the right person for the right job,” mandatory training, and collective wisdom in promotions. These systems emphasize discipline, continuous learning, and measurable performance—all principles largely absent in the current civil service framework.

The key questions at the heart of reform are simple but fundamental: should Pakistan’s civil service continue as a hierarchical, process-obsessed machine, or evolve into a system that is specialized, accountable, transparent, inclusive, and citizen-focused? The proposed answer lies in creating a SMART civil service—Specialized, Meritocratic, Accountable, Results-oriented, and Tech-enabled. This vision seeks to foster inspiring leadership, align postings with domain expertise, integrate digital platforms for transparent evaluations, and ensure diversity in recruitment and training.

To achieve this vision, the recommendations are extensive, but certain reforms stand out as crucial. First, the CSS recruitment system must be modernized into cluster-based exams, aligning candidates with relevant specializations rather than forcing generalists into every domain. Second, the inclusion of Urdu as a medium alongside English would broaden accessibility and equity. Third, the age limit for entry should be reasonably enhanced to attract both fresh graduates and professionals with practical experience. Fourth, lateral entry of experts from academia, industry, and technology is essential to plug skill gaps. Fifth, diversity quotas ensuring gender, regional, and class balance should be institutionalized. Sixth, recruitment should be digitized and time-bound to avoid bureaucratic delays. Seventh, performance evaluations must be linked to citizen-centric KPIs, with biannual reviews and multi-rater systems replacing the archaic ACR. Eighth, training must shift from rule-based to role-based, with modern pedagogy, expert-led instruction, and integration of cross-sector knowledge. Ninth, training outcomes should directly influence promotions and postings. Tenth, pay structures must be standardized and made competitive to attract high-quality candidates, especially in specialized sectors. Eleventh, underperformers must face structured exits, with transparent monetization of perks and benefits. Twelfth, institutional restructuring should reduce bureaucratic layers, enabling quicker decision-making. Thirteenth, citizen charters and service standards must be embedded into governance. Fourteenth, grievance redressal platforms modeled on global best practices should be introduced. Fifteenth, digitized dashboards and data-driven decision-making must become the default mode of governance.

Beyond recommendations, the heart of reform lies in realigning the bureaucracy with the state’s actual functions. The current structure, divided into cadre and ex-cadre groups under the 1973 rules, no longer matches the complexities of modern governance. General Financial Rules, PPRA regulations, and Rules of Business also require amendments to emphasize results-based budgeting, faster procurement, and modern accountability systems. Training academies and examinations must be redesigned around proposed clusters—administrative, financial, and information services—with domain-specific curricula and testing methods that evaluate both analytical and practical skills.

When compared to the existing rules and training regime, the contrast is stark. The current CSS system treats candidates as interchangeable generalists, assessed largely through outdated examinations and groomed under rigid hierarchies. The new cluster-based structure, however, seeks to match qualifications and aspirations with relevant fields, ensuring that specialists enter roles aligned with their expertise. The proposed system integrates modern subjects such as e-governance, data sciences, social media management, and disaster response, creating a pool of officers who are both versatile and specialized.

The future structure thus promises a departure from the colonial scaffolding toward a system that is citizen-oriented, merit-based, and globally competitive. With clusters of administrative, financial, and information services, alongside updated rules, revised trainings, and digitized platforms, Pakistan’s civil service can finally move from inertia to innovation. The real challenge is not in identifying the reforms—it is in overcoming the resistance to change. But if the steel frame of governance is to be rebuilt, the time for bold reform is now.

This article is based on an interactive session with Dr. Adnan Rafiq – member (Governance) planning commission and spearheading the committee of civil services reforms under the auspices of Federal Minister, Professor Ahsan Iqbal.

Siaf Ullah is an MPhil scholar of Public Policy at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE). His research interests include governance reform, institutional development, and Governance.